In 1909, a doctor revealed in a medical journal a secret he’d kept for more than two decades: When he was a student in the 1880s, he wrote, a wealthy couple had approached his adviser, a Philadelphia physician named Dr. Pancoast, complaining that they couldn’t conceive a child. The 31-year-old wife was examined by seven men (who must have been pretty thorough, as they even concluded she was capable of orgasm). Having determined that there was nothing wrong with her body, the doctor turned his attention to her husband, whose semen, examined under a microscope, appeared to contain no sperm. And so Dr. Pancoast performed one of the first documented successful acts of what we now call “donor-assisted” reproduction. The woman was sedated with chloroform while the doctor used a rubber syringe to inseminate her with a sample from the “best-looking member of the class.” She went on to give birth to a healthy child and thanked the doctor for working a miracle. Her husband eventually learned the mechanism of that miracle, but both he and the doctor agreed that his wife should never learn the truth.

From the start, conceiving a child with donor sperm was shrouded in secrecy, a dirty little detail to be swept under the rug. What did it matter how a baby was gotten as long as happy families were made? The practice spread quietly for much of the 20th century, often as the discreet handiwork of physicians using the sperm of a helpful medical student (or sometimes even their own) as part of an innovative “therapy” for male infertility. When members of the American Society for the Study of Sterility were surveyed in 1947 (shortly after the group was established), the majority said they approved of anonymous-donor conception. Some 568 women had been successfully inseminated that year.

Of course, little thought was given to how the children produced by these anonymous inseminations might feel about the secret of their parentage. With the mapping of the human genome still decades away, donor information was seen as largely inconsequential. Neither doctors nor parents thought these children might one day be faced with profound questions of identity and selfhood.

The emphasis on secrecy began to fade as the market for donor sperm shifted: In the ’80s and ’90s, while heterosexual couples began turning to IVF, single women and lesbian couples were increasingly looking for new ways to start families — and, without a dad on the scene to take credit for conception, they were more inclined to be open about a child’s donor origins. The first American sperm bank to offer “identity-release” donors (those willing to be contacted by their offspring) was a feminist nonprofit that opened in 1982.

Still, as sperm donation grew into a multi-million-dollar industry, donor insemination remained largely anonymous in America — unlike in the U.K., Canada, and many other countries, where it is subject to much more regulation. (The lack of regulation here, and the fact that sperm donors are paid, is partly why the U.S. is one of the largest exporters of sperm in the world.) In the U.S., clinics are not required to update donor or offspring medical information, to share any information they do receive, or to maintain records that accurately report the number of children produced by a given donor — one man could produce dozens of offspring. Because whatever medical history a clinic does possess tends to be self-reported, there’s the possibility of passing on mental illnesses and congenital defects that were undisclosed, undiagnosed, or unknown. And because donor-conceived children are considered the products of insemination rather than patients, they generally lack access to whatever medical records and information a clinic might possess, unless they have help from the patient in question — their mother.

But all of that has changed with the emergence of inexpensive genetic testing in the last decade. The direct-to-consumer DNA services like Gene by Gene and 23andMe have blown the lid off anonymity. Almost anyone can go online and find family. Initially the price of genetic testing through 23andMe was about $1,000, but today a basic kit costs $100 and offers a “DNA Relatives tool” where customers can opt to join a pool of 23andMe users who want to share their profile with others who’ve tested their DNA. Genetic testing and social networks have let donor-conceived people connect with “donor siblings” — others who were conceived using sperm from the same man — and in some cases, even the sperm donors themselves.

Innovation enabled the secrecy that first surrounded donor births; and now innovation is enabling transparency. The children conceived in the era of anonymous sperm donation have come of age and so have the tools to find out where they came from. Starting with one of the earliest examples we could find, we spoke to men and women born throughout the history of anonymous-donor conception — from a doctor-assisted “miracle” baby conceived during a snowstorm in the ’40s to the daughter of a single gay woman born in 2000. Some grew up knowing they were donor conceived; others were kept in the dark, discovered the truth, and decided to learn everything they could.

Culled from over 50 interviews with donor-conceived people, they are a study in the unstable chemistry of nature and nurture, the questions that parents can and can’t answer, and what, ultimately, defines us.

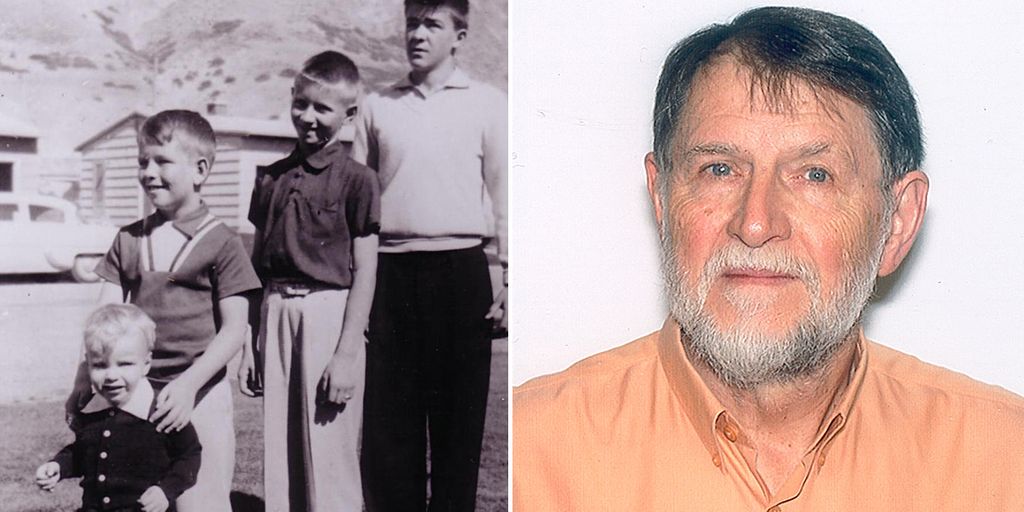

Bill Cordray

Conceived: November 6, 1944, 1:30 p.m.

Conceived at: Salt Lake Clinic

Born: July 1945

From age 13 I had a strong suspicion he wasn’t my dad. We were so different physically — he was real rugged with curly black hair; I was soft with straight blond hair — and we had such divergent interests. He was a laborer; I liked to sing, play music, and read literature. I wanted to be like him, though.

My dad and my brother died one year and four days apart. I was 37 at the time, and I told my mom I was worried I’d have an untimely death, too. That’s when she told me the truth. Dad was infertile — my brother and I were both donor conceived. Apparently a lot of men returned that way from the war, because of STDs, PTSD … I can’t believe they kept that secret from me for so long. I think she’d tried to hint at it, though, because when I was younger she gave me a copy of Aldous Huxley’s Island — that was my only reference for what artificial insemination even was.

The story was that the doctor had used a medical student. Four years after I found out, I worked up the courage to approach the OB/GYN. I was suspicious that he was my father, but he brushed it off. I think he recognized me. Three years ago, when I was 67, I found out — using a combination of genetic testing, social networking, and ancestry research — that the doctor was my father. I have made contact with 13 of my siblings and met 9 of them. One of my brothers looks so much like me he could be my twin.

Since I have connected with my siblings I have gained a much more complete sense of myself, my identity. But I wish I had met these people when I was young — I would not have suffered from all the toxicity of the secrecy if it had all been open from the outset.

Amanda Serenyi

Conceived: 1977

Conceived at: University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)

Born: March 1978

When I was 33, I asked my mom if my father was really my dad. My father had four children with his first wife, followed by a vasectomy; Mom desperately wanted kids, so she found a doctor who was “performing miracles.” The main aim was for a close physical match. Mom remembers being told there would be no records kept and that no one would ever have to know. My mom knows what it feels like to grow up in the dark: She’d spent her whole life obsessing over geneology because she didn’t know her dad. But that was my dad’s condition before he agreed.

After I found out, I’d look into the eyes of any man in his early 60s searching for some sort of resemblance. In 2012, I submitted a DNA sample to 23andMe, and after nine months I got a “predicted first cousin” notice. I zoned in on who might be my donor father; I Googled him and found pictures. I was electric with life after feeling dead inside for so long. He has daughters — my sisters — who resemble me. I stared at them, thinking: I’ve been in that pose, in a dress just like she’s wearing, with that same sassy smirk. This fantastic story of meeting them played out in my head.

I sent him a list along with pictures of myself — from childhood to my wedding — and said I wanted to get to know him. Turns out a man who donated sperm 39 years ago figuring it would never be traced back to him doesn’t want to be contacted, despite developments in direct-to-consumer DNA testing. He said, via email, I could contact him once a year for medical updates only. I was heartbroken. I still want to make contact with my sisters. My husband says he doesn’t want to watch me hit my head against a wall. But I have to maintain hope that someday I’ll meet him and his daughters, my biological family.

Lise Johnson

Conceived at: University of Alberta, Edmonton

Born: 1980s

As a recently married liberal queer woman, my partner and I are constantly fielding the baby question. When are you two having kids? people ask innocently. We suffer from knowing too much about our options. My partner is a Korean-Japanese woman adopted to Caucasian parents. And I’m donor conceived.

The tipping point for me was watching the film The Kids Are All Right. Some of my friends identified with the gay mothers, but I saw my donor-conceived perspective played out for the first time. I connected with the children. I was jealous of these fictitious kids who found their donor father. Even if he wasn’t as great as Mark Ruffalo, I wanted to know who mine was. When I called the clinic I became acutely aware I had no rights: They would not give me any information. It took me almost eight years to convince my mother to call.

I think it was very difficult for her to hear that I wanted to know so much. I hear the same perspective from some of my friends who have used donor sperm. At first they are ready to take a very open approach, but that changes. They feel really threatened by the father. And this is the thing people really don’t want to hear: They want to take the word “father” away, but you can’t get away from the fact that you have half of someone’s DNA.

When I talk to my gay friends I ask: Why are you doing this instead of adopting? If they mention anything about wanting to be connected through genetics or DNA I say, Yes, and that is what your child will want, too. We want that connection with our parents just as much as you want connection with your child.

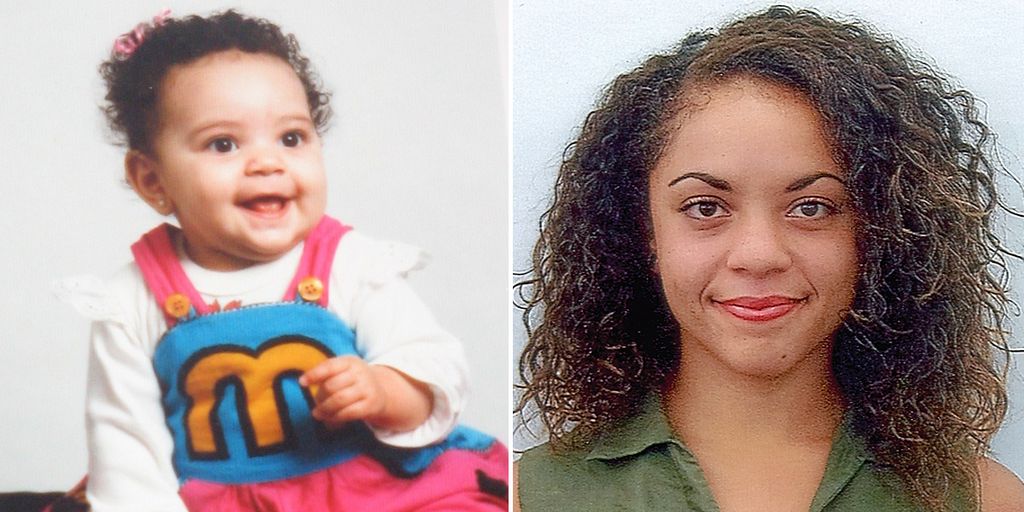

Patrice

Conceived: 1981

Conceived at: Stanford Fertility Clinic

Born: 1982

My mom was swayed by the argument that it wasn’t a good idea to tell me and my sister, who’s three years younger and was donor conceived, too. I wasn’t ever angry at her — she said that she really didn’t want this to be a secret. People convinced her it was a good idea.

She told me after my parents had divorced and I’d left for college, and it took me about six months to come to terms with it. I felt like my life was a lie. My childhood was over. I stared in the mirror wondering where the features on my face came from. Where did I get those dimples?

Some years after I found out about my conception I felt compelled to search for my biological dad. I wrote to the doctor at the fertility clinic and chased a hundred different dead-ends. Other years, I accepted “not knowing” as my reality and went about the rest of my life. When I had a son I felt like I had to find my biological dad — and by that point, technology had advanced.

I found a cousin, my biological father’s nephew, and we talked on the phone. He said his uncle died in 1996, when I would have been 14 — before I even knew he existed. I was sad, but also relieved. It would have been so nice to meet him, but it took the pressure off. His family very recently sent me a few old photos. I look just like him.

Rachel

Conceived: 1982

Conceived at: Private doctor’s office in Denver, Colorado

Born: 1983

Mom had me when she was 39. She was a single psychologist — she did her Ph.D. dissertation on kids who grew up without fathers. She looked into adoption, but they didn’t want single moms.

It was never a secret. I always knew my story, and I always felt like I could talk to her about it. In elementary school I was very proud of my origins. It’s probably because my mom’s a shrink who was really careful about the narrative. Years later she told me that my teacher had said, You might want to tell Rachel to keep that on the DL, people could think that’s weird. Things took a turn in middle school — I got called “test-tube baby” and “freak.” I changed schools and kept my conception secret after that.

When I was growing up movies like The Parent Trap always impacted me. I’d think: I must have a twin out there! When I was in my mid-20s I found the donor-sibling registry and I immediately thought, Maybe I do have a little brother? But after spending time online hearing all these heartbreaking stories of being lied to or searching forever, I decided that I don’t know what I would gain from looking for family members. The man who did this didn’t want to be known. I have rights, yes, but he does, too.

I had a friend in middle school who was adopted. She had two parents who loved her a lot, but she would cry at lunch almost every day saying she didn’t know who she was. I was like: How will meeting these people tell you that?

Victoria

Conceived at: clinic in central Virginia

Born: mid-1980s

I located my donor father using a combination of DNA testing and the family trees that our mutual relatives had created online. I also found my sister that way I received a message from a woman on 23andMe who was listed as my “half-sister” according to the site. Before that, she didn’t know she was donor conceived as well. People ask, Do you feel like she’s really your sister? And I guess I actually do. We look alike; she’s exactly the same height as me. We have very similar interests. I think about her and want her to be happy. I love her. When it comes to my “donor father” too, in a lot of ways, I do feel like he’s my father.

I use the idea of life on other planets as an analogy. We all know that it’s extremely unlikely that Earth is the only planet in the universe that has intelligent life, but we are all resigned to the fact that this is something we will probably never know for sure in our lifetimes. Now it feels like I’ve made first contact with an alien civilization, and they’re a lot like me. For instance, from a very young age I have been absolutely obsessed with reading. My family viewed me as kind of strange. My quirks — like my love of sci-fi and fantasy — were accepted, but not really celebrated. Then I get to my genetic father John’s house, and he has tons of books, including several by one of my personal heroes, Carl Sagan. There are lots of other little examples like that too. Added together, they are undeniable evidence of kinship. The whole thing has really strengthened my sense of identity and place, and I think it’s made me a better person.

I know my experience has been about as positive as anyone could expect, and for that I’m really grateful. However, I do think that the personality dimension of “openness to experience” is something that is at least partially heritable. I’m a little sad that I didn’t know them all until I was over 30, and I do wonder what it would have been like if we had grown up together. But mostly I’m just happy to have found them. I feel like I’ve been a detective in my own life and gone on an adventure. I hope that there are even more of us out there, and that I get to find them in the future.

Rob Hunter

Conceived: 1984

Conceived at: University Hospital Clinic in London, Ontario

Born: April 1985

My grandmother told me just after I graduated university. When I confronted my mom she explained that they had been on the adoption list for years. She said she would drive past houses and see diapers drying in people’s yards and have to pull over to weep because she wanted a baby so bad. Their doctor suggested they visit this “clinic.”

Here’s the irony of human behavior: I’ve known for eight and a half years and I haven’t done much. It took two years before I had “the conversation” with my dad. He was crying because he was scared I would reject him. That’s part of the reason my mother didn’t tell me. After a two-hour tearful conversation, we never spoke of it again. He passed away not long after.

In 2008 I did one of the very early DNA tests and joined family-tree databases. I ordered graduation pictures of the medical-school class at the university where I was conceived … I should make the calls.

Without sounding like I have delusions of grandeur, I will say that I have always thought I’m unique. I was an entrepreneur from a young age. When I was 14, I started selling Japanese wrestling videos online. I opened an ice-cream franchise when I was 22. Learning about my paternity reinforced my uniqueness. A few years ago I was at a breakfast meeting with a Silicon Valley venture capitalist, and he said a lot of big-name entrepreneurs weren’t raised by their birth fathers — Steve Jobs being the most obvious. He also said many successful businessmen were donor conceived.

I think if we are going to continue to do this, as a society, we just have to be transparent. The logic at the time was don’t tell, don’t tell, don’t tell. There should be a media campaign saying, look, we screwed up.

Matt Doran

Conceived: 1986

Conceived at: University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC)

Born: December 1986

There’s a man known as “Dr. Papa, father of the decade,” he’s rumored to have had over 500 children. That’s my father. And I call him “my father” because that’s who he is, that’s how I see him.

Like many kids conceived by heterosexual parents in the ’70s and ’80s, it was kept a secret from me until I was an adult. When I was 25, my wife and I were having our first child, and I was at the sonogram where you hear the heartbeat, looking at my baby in my wife’s womb, when it struck me: I need to ask my dad how I was conceived. I never felt like we connected or had anything in common physically or intellectually. I was right.

I scoured the internet looking for resources — there wasn’t really much out there to support people who were conceived this way. In 2013, I launched my own social network, DonorChildren.com.

These men got praise and money for supposedly making people happy, but nobody really thought about the ethical consequences and how it would impact the kids they made. My father sold sperm for a decade and drove a sports car to college. But I feel pity for him. His father died when he was a kid. Maybe his way of dealing with it was to proliferate himself through the world using his sperm — not that I am trying to justify what he did.

I’m an aerospace engineer, literally a rocket scientist. I never knew why I took that path. Now I know that five generations of my paternal family worked in aviation and engineering. When I contacted him he said: I gave you the gift of life. You should be thankful. I gave you superior genes. Then he cut me off.

When you’re created this way, you have a lot of expectations placed on you — you’re the trophy child. Looking back, I think I felt that pressure, but I didn’t understand why. Now I’m a father myself so I know that sometimes I feel like my kids are objects, in a way. Parenthood is a selfish and selfless kind of love. And it’s hard knowing that my kids won’t know most of their cousins, their aunts, their uncles, their grandparents … they probably have thousands.

Courtney McKinney

Conceived: 1989

Conceived at: California Cryobank

Born: November 1989

I was raised by a single mom in a black family, but I’m lighter than everyone else. My mom would say: Black people come in all shades! When she was pregnant, she made a video explaining everything, and she gave it to me when I was 16. When I found out the truth I said: Why didn’t you get a black donor? She said there weren’t any. People like to say: Everyone deserves a biological child. And I agree. But that should not be at the expense of considering what their kids will want. I guess it shows that the desire to have her own child must have been very strong.

I was raised in suburban Dallas and I did a lot of activities with white people; I saw that wealth and fun were for white people. My black family didn’t have that privilege. I felt like I was part white, I think, deep down.

I don’t want a dad — and the fact that my donor doesn’t want contact with me doesn’t make me think less of him. I just imagine him as a college kid who really needed money. My donor number is 1047. I had a friend sketch a tattoo design, but I haven’t yet had the desire to put it on my body.

I feel like I am one of the most American concoctions of a human on this planet. Being the descendant of slaves, slave owners, and Native Americans from the side I do know is part of it — but the other element is that I am a product of unchecked capitalism, and the idea that all is fair in the name of profit. Few have such a personal connection to our Wild West style of business as children of anonymous donors.

Joshua David Gutterman Tranen

Conceived: 1993

Conceived at: Doctor’s office in Columbus, OH

Born: May 1994

My mothers met at a radical lesbian feminist festival. They didn’t want a donor they knew because they didn’t want a “father” coming into the family. They are big on queer kinship: Biology does not equate with family. The sperm bank they used only offered total anonymity, which is what they wanted anyway.

In the last few years there has been a big movement of donor-conceived children reaching out to their “half-siblings.” Personally, I contest the use of the word “sibling” to talk about these other donor-conceived kin. We need new language to talk about donor-related folk.

My mom who gave birth to me says, Fatherhood is more than semen! I don’t remember a time that I didn’t know about my donor, so my parents must have sat me down when I was really young and explained it. But I also should say that I haven’t always been as comfortable as I am now. We live in a society that values masculinity and fatherhood to an extreme, and as a young boy growing up in my all-female family system, I often daydreamed about my donor, and did imagine him as a father figure. And I’m also queer, so I’ve always had a bit of a contentious relationship with masculinity. But over time I’ve learned that the figure of the father is just another cultural fixation.

Breannen

Conceived: 1994

Conceived at: Fertility Treatment Center in Tempe, AZ

Born: July 1995

My mother was 39 and single and she wanted a child. She’d had several failed attempts, including a late-term miscarriage. I always knew that I was donor conceived — my mom never kept that from me. But when I started looking, in my senior year of high school, I realized that all the records that could have helped me had been lost.

Why is it that when you can’t have something you want it more? This man is a shadow in my mind. He’s nothing to me and yet he’s everything. I know he was Caucasian but that’s about it. There are certain traits that I know I must get from him because I can’t see them anywhere on my mom’s side of the family — like the shape of my lips. When I try to imagine him I picture a generic white man who looks like nobody and everybody at the same time.

I have two younger siblings who have no genetic relation to me (my mom adopted them) but we have some of the same mannerisms, some of the same likes and dislikes. We are related through our environment. I think there’s something deeper that made the blueprint for how I would react to things, though, and that’s why finding half-siblings is so important to me.

Connecting with other donor-conceived people online has given me some comfort, but I also find so many are anti-reproductive technology, anti-same sex couples, anti-single women having kids. Sometimes I will engage, and say: Hey, do you realize that without all this you wouldn’t be here? Some reply and say: I realize that, but it doesn’t make it right. Others say, Yeah, I guess I just need to vent. I need to be angry with someone.

I think everybody who’s donor conceived has thought about accidentally falling in love with a relative or discovering millions of siblings. But I’m worried about the opposite: That I’m here all alone.

Maureen Kesteron-Yates

Conceived: 1995

Conceived at: Obstetrical and Gynecological Associates (OGA) in Houston, TX

Born: 1996

I was raised by two moms. I can’t pinpoint what made me start looking for my donor — one day I was like, You know, this is important to me, and I don’t understand why. I’ve said to my nonbiological mom: I don’t want you to think that I don’t love you, and I don’t want you to think I’m trying to replace you. She’s the person I’m afraid I’m going to hurt.

A lot of people are against sperm donors completely. I have a hard time with that because I wouldn’t be here without it. My parents say things things like, Oh, you were almost a Hispanic baby — which makes me realize they didn’t think very hard about how much that would have distanced me from the rest of the family. I think if I have kids I would adopt. Adoption is giving back.

I do think information should be more accessible. I keep the bullet points about my donor on all my devices. Here’s what I know: He has degrees from Yale and Rice University. He’s an electrical engineer. He has light-brown to dark-blond hair. It legit says, “pretty blue eyes.” Pretty blue eyes! Married with a seven-year-old son. (But it doesn’t say when he was born — is he seven now? was he seven when I was conceived? when was he seven?) He likes to read; I like to read, too. He loves music, film, theater, and photography. I also really love all those things. He likes classical music and he’s got a dog and a cat … so do I. At first, this information was comforting because he has so many interests that are similar to mine. But when I realized that was all I was getting I felt so frustrated.

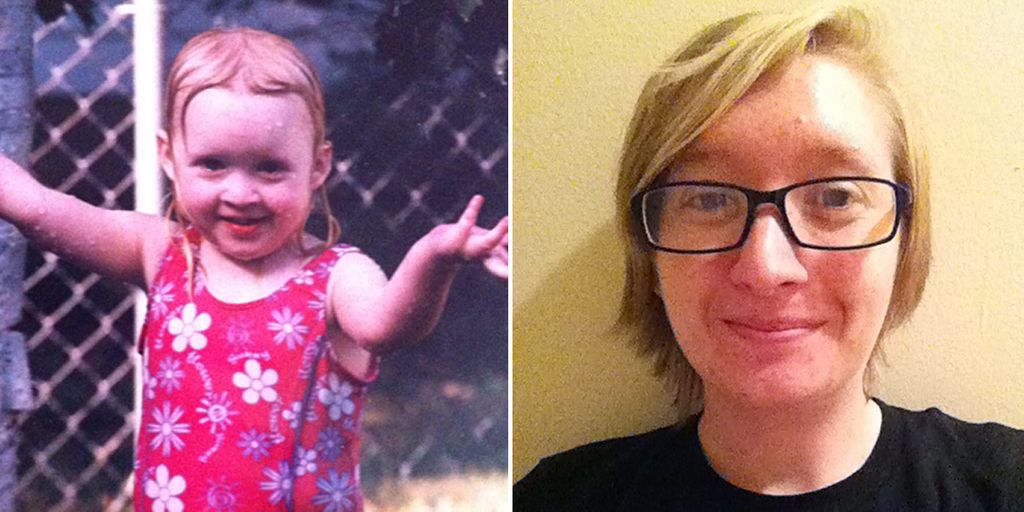

Hattie Hart

Conceived: 1998

Conceived in: Oklahoma City

Born: 1999

I remember I was 14, riding in the car with my mom, and she got a text and asked me to read it to her, because she was driving. It was her husband, soon to be ex-husband, saying: I think we should tell her now. Like, what is he talking about? Tell me what? She takes a really deep breath and she goes, Steve is not your biological father.

I’m generally a really happy and positive person, but my mother will tell you that period was devastating. I had a recurring nightmare that the clinic had burned my file. They wouldn’t give me anything because I wasn’t the recipient of the sperm. I’m like: I am the sperm.

Then we discovered the Donor Sibling Registry — I had to save up to pay and join. It turned out I have three half-siblings. My mom was so supportive, she really helped me with my search. One day my mom was messing around on the Donor Sibling Registry, and tried a keyword search for Choctaw because his genetic heritage noted he was part Choctaw Indian. He was the only match. The timing all made sense. Later I typed the info I had about this man into Google and the first hit was a Wikipedia page of this football player and everything matched the information in my papers. I was dry-heaving in front of my laptop, in tears.

When I wrote to him I was like, Well, this is who I am. I’m not after money, but I’m really interested in knowing my genetic heritage. That night he called me and we spoke for three hours. I asked if he ever thought about the children he’d basically donated. He said not until one of the mothers sent a picture of her son and he looked just like him. He came to visit me for a weekend and I remember he said: I want you to ask me everything that you want to know right now because I plan on having a relationship with you, but in case something does happen to me, I don’t want it to be like my father, who died before I could ask the questions I wanted to.

Danica Torrens

Conceived: 1999

Conceived at: Institut de Pathologie et de Génétique in Loverval, Belgium

Born: February 2000

Mom is gay and single, and she wanted a child. I think she would have liked to have raised me with a partner, but she wasn’t going to wait — and she was 37. She didn’t even tell the doctor about her sexuality, because at the time being a single mom was enough of a stigma. I don’t really refer to him as “Dad,” just my donor. I’ve never had a desire to know him.

Mom explained things to me using Our Story, a kid’s book published by the donor-conception network in England. Mom never hid my conception. She would say, Some very nice men gave their sperm away so that mummies like me can have babies like you. In kindergarten a woman kept asking me, Where’s your dad? You must have a dad! Mom says I sat in the back of the car, sighed, and said, She just doesn’t get it! When I was about 5 a bunch of kids surrounded me demanding to know, Who’s your daddy? I said Spider-Man; they were like, Oh, okay!

Because nobody ever asks donor-conceived kids what we think, they make assumptions, and one of them is that we have suffered loss or grew up in sad situations. Personally, I think that a woman choosing to have a baby through donor conception — when she knows that she will love it with all her heart — is not selfish.

Society is evolving and becoming more accepting. “Normal” isn’t really … anything anymore. A family is a family, no matter the “situation.” Mom made me feel happy and safe, and that’s what families are for.

*Some names have been changed throughout.