When I was a teenager in the early 2000s, my parents gave me a digital camera. I used it to photograph my friends hanging out at school; trying on dresses at the mall; and driving aimless circles around our hometown. You know, teen stuff. At some point, I uploaded the entire archive to Flickr, adding new albums every few weeks as I embarked on college. Eventually, though, my digital life migrated to Facebook and I forgot Flickr completely.

Then, last winter, I found it again.

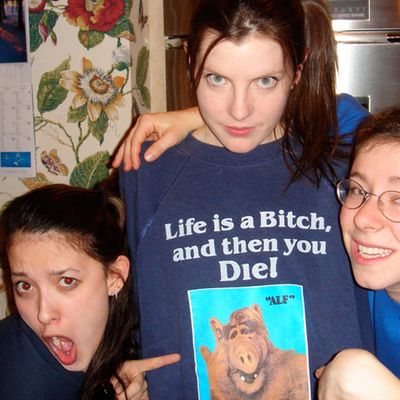

I was performing an unrelated Google search and ended up at the old photo-sharing website. To my surprise, I was already signed in. (Some ancient, automated Yahoo login had carried over.) There before my eyes were 6.4 gigabytes of exuberantly ugly photos from my youth: Midwestern teenagers with acne-laced faces and ill-fitting jeans, making kissy faces in food courts and flashing each other in the backs of cars. Ten years later, I could not believe the racy material I’d thoughtlessly made public. One album, entitled “My friends keep stealing my camera,” consisted entirely of self-shot pictures of two friends’ boobs and butts. Frantically, I searched Flickr’s FAQ for instructions on mass photo deletion, all the while wondering if I was a child pornographer.

Then I noticed my inbox. I had FlickrMail. For close to a decade, men who I can only assume were searching Flickr for pictures tagged “tits,” “ass,” and “homeroom,” had been messaging me. They were wondering where the permanently youthful girls in those photos lived. If we wanted to be models. If my hair were still that length.

I thought of this episode when, this month, dozens of female celebrities’ iCloud photo archives were hacked, prompting journalists to profile tribes of young men on the internet who have made into sport the hunt for naked pictures of celebrities, classmates, acquaintances, ex-girlfriends. That today’s internet is a reputation-ruining powder keg packed with compromising photos, embarrassing emails, and unwise social-media utterances has been extensively documented. And yet every year, the past comes back in new and newly terrorizing ways, no matter how much time I spent in the previous year trying to lock it down. As I waited for a “batch edit” to the privacy settings of 500 Flickr pictures to go through, I began to wonder if the data itself didn’t have some sort of survival instinct. My data was multiplying, and when I try to delete my data, it seemed to fight back with Byzantine (and humiliating) deletion procedures requiring defunct email addresses and passwords.

Sometimes, of course, digital déjà vu is welcome and cherished. (Perhaps too cherished. Every #throwbackthursday, I wonder whether we are trapped in a vicious cycle of nostalgia.) But in my experience, for every cherished photo that pops back up, two dozen awkward throwaways surface too. What’s more, the accruing of photographic junk happens very quickly. When I back up my phone, I always discover pictures I thought I deleted — images where people are blinking, a series of incrementally shifting photo crops, a filter I tried but didn’t like. For a while, these images would appear in a pop-up thumbnail display every time I plugged my phone into my computer, which was strange because I could never find them in the phone. I had reached the point where my devices, apps, and cloud-storage systems were communicating so seamlessly, they actually had more dirt on me than I had on myself.

When actress Mary E. Winstead’s photos appeared in the first mass leak, she tweeted, “Knowing those photos were deleted long ago, I can only imagine the creepy effort that went into this.” And “creepy effort” is right: Valleywag’s post-leak report on iCloud-hacking message boards revealed men who said they returned, obsessively and invisibly, to the same women’s iCloud accounts over the course of years, waiting for new backups to appear — backups the women might not have even known about, if their technology-use habits were anything like mine.

And so, as America debated the political and legal implications of the mass violation of celebrity selfies, I reacted in the most selfish way one can react to a scandal that requires interested parties to use the word selfie repeatedly: I embarked on a quest to reckon with all of mine, and those of any innocent friends caught in the crosshairs. There is a finite quantity of digital data in this world that I control, I reasoned, and I should be able to log into every cloud and review every photo. That which I keep should be willfully chosen; that which I do not want should be gone forever. The task wasn’t just about naked pictures. (Though clearly those would trigger alarms.) It was about control. Control and freedom.

It was the most arduous thing I have ever done on the internet. More arduous than navigating Con Edison’s bill-pay website. More arduous than an Obamacare insurance exchange. (The fact that I had to request something like a dozen username reminders, then reset as many passwords, did not help. If Sisyphus lived today, he would be chained to a computer clicking hyperlinks to reset his password and sign back in, all day long.) In the age of cloud-computing, deleting pictures is like slaying the hydra: Every time you kill one archive, you discover two more. Photos were hiding not just in my iPhone’s Camera Roll, but in every photo-editing, messaging, and dating app I’d ever downloaded. Photos were lingering in ancient text-message threads. Shared photo albums I’d forgottenhad been updating without my knowledge. I felt like the Donald Rumsfeld of selfies: There were known knowns (caches I knew to review) and known unknowns (apps I suddenly realized might be saving photos) and unknown unknowns that I could not anticipate but will surely terrorize me later (a fear that the Xbox Kinect motion camera will someday unleash hours of clumsy Dance Central 3 footage keeps me up at night).

Because though nefarious hackers and vengeful exes may, in theory, have the ability to weaponize private material by forcibly decontextualizing it, the mere passing of time can do it, too. There was a time, once, when the conventional wisdom on nudie-pic scandals was that the person who posed for the picture was a fool. Today those critics are themselves criticized, for blaming the victim and for failing to acknowledge reality. For whatever reason, some strange fluke of the human psyche compels us to document our most idiotic moments, to think we look hot even when we look shitty, and to pursue sexiness in spite of astonishingly high risks of looking a fool. The photos in my forgotten Flickr account were horrible, in part, because they documented flukes of the psyche that no longer made sense to me. The pictures in “My friends keep stealing my camera” were taken as a sort of joke on me (Ha-ha, Maureen will see our crotches when she turns her camera on), which I then posted on Flickr as a joke on them (Ha-ha, I am acknowledging your crotches by turning them into a high-resolution photo album which only we will see). Upskirt and selfie weren’t in our lexicons back then, but today someone who viewed those pictures would likely identify them as both.

Not that anyone will ever have the chance to. I deleted it all. I think.