Women who achieve lofty positions in politics or business often find themselves facing a particular (and predictably brutal) publicity cycle. It goes like this: Get dolled up for Vogue, then get trashed online. Critics are all but guaranteed to decry a powerful woman’s appearance in a women’s magazine as a backward step, a concession to the demands of sexist, elitist fluff, be it Debbie Wasserman Schultz, Marissa Mayer, or Wendy Davis.

Most recently, Politico declared that “women’s magazines demean powerful women — even when they’re trying to celebrate them,” a dynamic Politico referred to as “the princess effect.” Writer Sarah Kendzior argued that former Obama staffer Alyssa Mastromonaco’s new gig as a Marie Claire contributing editor symbolized an intellectual flattening of women perpetrated by the media on the whole. “The personal is political,” she wrote, “but for women, the political is removed from the person, replaced by trite obsessions with clothes, hair, child care choices and exercise routines.” On one hand, it’s nice to see people questioning the media’s gendered assumptions and expectations. (Why should women — and not men — always have to answer questions about work-life balance or personal style?) But by dismissing women’s magazines and their concerns as inherently trivial, arguments like Kendzior’s perpetuate sexism in a different way. That’s why it’s so heartening to see some powerful women siding with the supposedly demeaning lady mags — and publicly defending that choice. After all, why should we consider clothes and child care such insulting topics in the first place? Why shouldn’t those conversations coexist with ambition and professional accomplishments?

On Friday, Mastromonaco fired back at Politico in the Washington Post. “If we really want to talk honestly about ‘having it all,’” she wrote, “we need to start by according a woman’s many interests outside the office with the same deference we do a man’s.” It’s only fair: A male politician’s interest in sports makes him relatable, not lightweight. And men’s magazines aren’t dismissed when they feature “supposedly hard-hitting pieces adjacent to features on golf swings, pinstripes and bikini babes,” as Mastromonaco put it.

Meanwhile, former New York Times editor Jill Abramson chose Cosmopolitan for her first interview post-ouster. The decision was simple, she said: That’s where her preferred journalists were. “Reporters I won’t talk to say media blitz of course,” Abramson texted her daughter. “No one notices I’m just choosing women I think kick ass to do the interviews.” That women who kick ass are working for the sex bible Cosmo reflects a concerted effort on the part of editor Joanna Coles to beef up political coverage, correcting the dearth of so-called serious journalism in women’s magazines bemoaned by Jessica Grose in The New Republic — and, more important, making the magazine better reflect the full spectrum of women’s interests. (Turns out they look a lot like men’s interests: sex, stuff to buy, careers, pop culture, and world affairs.) Like Coles, Mastromonaco wrote that she took the Marie Claire job for “the prospect of helping to shape these incredibly important and germane conversations.” But it’s hard for women’s magazines to realize this feminist goal when, every time they try, critics insist that the magazines are dragging their subjects down rather than broadening their own interests.

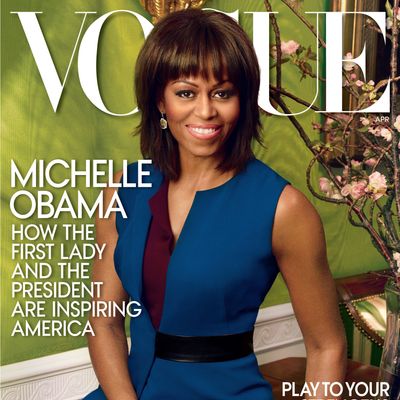

Why doesn’t Mastromonaco’s hire instead symbolize women’s magazines growing commitment to dissolving the gendered boundary between the frivolous and the serious? I see this happening in outlets beyond Marie Claire. GQ’s profile of Ted Cruz opened with a description of his “black ostrich-skin cowboy boots” and the Cut covered Paul Ryan’s shoes, Mitt Romney’s jeans, and Rand Paul’s filibuster-fashion advice. Even in Vogue, powerful women may now unapologetically embrace or reject the more superficial aspects of magazine-making. Four years ago, during her first presidential bid, Hillary Clinton declined to sit for a “feminine” Vogue photoshoot, a decision that caused Anna Wintour righteous dismay. But in the lead-up to Clinton’s presumed second bid, Vogue published the first excerpt of her memoir, no photoshoot required. In doing so, the magazine demonstrated their trust that women want to hear Clinton’s thoughts, with or without a princess-y fashion spread.

It excites me equally to see powerful women demand the right to be “fashionable and informed,” as Mastromonaco put it, and to refuse fashion wholesale, like Clinton. But I think we could go further. Fashion, after all, isn’t totally extracurricular. As long as we all need to get dressed each morning, clothing will be a communication tool. (I like to imagine Vogue editorials as a monthly digest of new and very expensive emoji.) Men and women both choose how they deploy the language of fashion; but women, deprived of the suit-as-uniform, still face unique challenges in fashion fluency. (When President Obama repeated an outfit, Vanity Fair praised him for conserving his mental energy for more important tasks. When Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen did it, Roll Call begged someone to “spot her some new threads.”) Women’s magazines — especially when they work with women like Clinton, Abramson, and Mastromonaco — offer other women a map for navigating style and other sexist minefields without compromising their intellectual integrity. For that, we should celebrate them. And if we want to level the playing field, we should start by posing the same “frivolous” questions of men.